Stories

The knifeman always calls twice

Who could have forseen the fate of my sons?

They say there's no cure for a broken heart. Staring at my son Billy, 16, pushing his food around his plate, I knew that better than most.

‘Just try a bit of the mash,' I urged. His sad, blue eyes looked up at me.

‘I'm just not hungry, Mum,' he said. Sliding his plate aside, he went upstairs to his room.

It wasn't just his appetite for food my boy had lost, but his appetite for life.

We'd all been left devastated the year before when my eldest son David, 18, had been killed in a mindless attack.

He was walking a pal home with his girlfriend Tracey, 17, when he'd strayed into the path of a local gang.

I'd seen him just minutes before on my way home from bingo. ‘Take care,' I'd smiled. But, only 15 minutes later, Tracey rang. ‘It's David!' she screamed. ‘He's been stabbed.'

Horrified, me and my husband Dave rushed through the streets to find our boy sprawled on the ground as paramedics worked frantically to save him. I'd sunk to my knees beside him.

‘David, wake up!' I'd begged, cradling him in my arms. He opened his eyes one last time before being pronounced dead at hospital. They were such dark days.

After that, I spent most of my time sobbing on David's bed. Our only chink of light was when, two weeks later, Tracey gave birth to their daughter Jordyn.

‘David will always live on in her,' I had vowed. But now, as

I cleared Billy's plate, I wondered if any of us would ever get over the loss of his only sibling. Born just three years apart, David and Billy had been peas in a pod, not even complaining when I dressed them in matching outfits as kids.

They were different - Billy, blond and loud, David dark and quieter. But Billy worshipped his big bruv.

They were different - Billy, blond and loud, David dark and quieter. But Billy worshipped his big bruv.‘I want to learn to play snooker like David,' he'd said, following his brother to the local club and chasing him around on his bike.

Thinking back to that terrible night when I had to break the news to Billy - who was just 15 - that his brother was dead, still moved me to tears.

‘You're lying!' he'd raged, smashing plates in the kitchen.

Billy still pined for his brother. ‘What are you doing going out at this time of night?' I asked a few days later, catching him going out in the early hours.

‘I'm going to the cemetery,' he'd shrugged. ‘I want to be with David.' Every part of me ached to pull him close and stop him, but I knew this was his way of dealing with his grief.

Over those next few years, Billy cut a forlorn figure as we celebrated David's birthday each year by lighting candles on the spot he was killed.

One small consolation was watching Jordyn grow up.

‘She's the spit of David as a child,' I'd sighed to Billy one day when she was five and had popped round with Tracey.

‘She's got that same dark hair and those eyes,' he'd smiled.

Then a wicked grin spread across his face. ‘Remember that time David lifted up his trouser leg and told us his hair only grew on one leg?' Billy chuckled.

Tracey laughed, cuddling Jordyn. I wished I could have cuddled Billy like that. He was the only child I had left now.

Instead, consumed with grief, he'd often get into fights. And one night, when Billy was 24, I panicked when he wasn't home by 11pm - the time David had been killed all those years ago.

I went out searching the streets, finding him a few minutes later with pals.

‘Stop fretting, Mum,' he'd smiled, linking arms as we walked home. ‘I'm a big boy now.' But still, I waited up for him every night.

It was me who leant on him four years later, though, when I was diagnosed with breast cancer and needed an op to remove the tumour, followed by chemo and radiotherapy.

‘I couldn't bear it if anything happened to you, too,' Billy fretted, making my tea.

‘Don't worry, love,' I promised. ‘I'm not planning on going anywhere.' My treatment was gruelling and, by now, Billy was acting as a carer for Dave, who'd had a disc removed from his spine and struggled to walk.

‘You know, I think our Billy's turned a corner,' I smiled at Dave one evening. ‘At one point, he was so broken I thought he was going to commit suicide,' Dave admitted. ‘But he's really turning his life around.'

The following year, Billy moved into a council flat of his own. ‘Every inch of me wants to keep him with us,' I sighed to Dave. ‘He has to live his own life,' he soothed.

‘I know,' I smiled. ‘I'll just miss him, I guess...'

Billy had soon settled into his new place, though. ‘Don't forget, you're still my little boy,' I teased, as he showed me the new wallpaper he'd put up.

The following year, just two months before the 16th anniversary of David's death, Dave and I decided to go away to a friend's apartment in Benidorm. Being at home at that time of year just brought back too many painful memories.

‘Come with us,' I insisted to Billy, a few days before we were due to fly out.

‘If I can get a cheap flight out, I'll be there,' he promised.

He was like a different lad these days, staying in most nights. Though he always seemed to have a different girlfriend!

‘Ever want to settle down?' I'd tease. ‘I want marriage, kids, the lot,' he'd reply. ‘And I'll get it one day, too...'

Days later, me and Dave flew out to Benidorm. We'd only been at our apartment for two hours when my mobile rang. It was my brother Tom, 60.

‘Sheena,' he started, his voice clearly distressed. ‘It's Billy...'

My stomach lurched. I'd had a call like this before, 16 years ago. ‘What's wrong?' I asked. ‘Sheena, just get yourself home,' Tom insisted. ‘I'll tell you everything then...'

At that exact moment, my battery gave out, but I'd heard enough. ‘Oh God. It's Billy!' I wept to Dave. ‘He's dead!'

He desperately tried to calm me down. ‘He didn't say that, did he?' he asked. But his tone told me he feared the worst, too.

It wasn't until the next day that we could arrange a flight home. Back at Glasgow airport, two police officers were waiting for us.

‘There's no need for you to go through passport control,' one said gently, ushering us out of the queue. And in that moment, I knew my boy was gone. Both my babies were gone. The officers wanted us to go the police station but, desperate to delay the inevitable, I insisted a friend drove us home first and there Tom and other heartbroken relatives were waiting.

‘It's Billy,' Tom confirmed. ‘He's dead...'

Now it felt like I was drowning. ‘Please, no,' I begged, collapsing. ‘Not both my babies.'

I listened, dazed, as a throng of voices tried to explain.

There had been a bonfire party on the night we'd left for Spain. Billy had gone to watch, along with his friend William Bendoris and a few others.

‘Some youths were drinking and urinating into the fire and trying to get Billy and his friends to join in, but they wouldn't,' one of my friends explained.

Not long after, four guys - some of them with their faces covered by masks - chased Billy down the street and launched a brutal attack in full view of passers-by, including children.

Tom and my other brother Neilly, 57, had identified Billy's body. But I had to see my boy.

Like a sick action replay of the day my David was killed, we were taken to the morgue to see Billy. But his body was in a worse state than his brother's had been, because the assault had been even more ferocious.

I shuddered as I looked at Billy's face, turned to one side because the other had been slashed. Over those next days the full horror inflicted on my boy was revealed.

‘His killers stabbed him in the back, trying to sever his spine and sliced through his liver and kidneys,' a police officer admitted.

One blow had even sliced his heart in two.

‘What sort of monsters would do this? ‘I sobbed.

We were told the attack had followed a misunderstanding during which one of the relatives of the boys suspected had been threatened at a nearby takeaway.

But Billy hadn't been involved, and by the time these lads killed him, they knew that.

Within 48 hours of the murder, we'd been given the names of four men who had apparently killed our son.

They were local lads Billy had known all his life. ‘Every single one of them was at David's funeral,' Dave said, sadly.

Thankfully, within three weeks, police charged them with Billy's murder.

A month later, we were given his body back for burial and held a wake in his bedroom.

‘Don't kiss or touch the left side of his face or it will collapse,' the undertaker warned.

We buried Billy next to his beloved brother with a picture

of the two of them and a letter, just like I'd done with David.

‘I can't believe I've lost you both,' I wrote. All I could do now was pray for justice.

A few days after the case opened in August, charges against one of the accused were dropped, but the other three would stand trial for Billy's murder. Steven Evans, 28, Christopher Harrison, 20, and his cousin Daniel Harrison, 16, denied everything.

As I turned up at the High Court in Glasgow, the sneering smiles from their friends and family cut through me.

William Lindsay, a friend of Billy's who'd been at the bonfire, told the court that he'd seen the attack. But a week in to the trial, I could bear no more and stayed at home.

Just four days later though, the verdict was delivered.

Just four days later though, the verdict was delivered.‘Guilty!' Dave whooped down the phone, cheers ringing in the background. ‘All three of them.' I cried tears of pure relief.

David's killer was convicted of culpable homicide and served a pathetic three years. But the judge had apparently told Billy's killers: ‘You have been convicted of a vicious killing carried out with monstrous brutality and ferocity... I am bound to pass a form of sentence that will result in your detention for life.'

Steven Evans and Christopher Harrison were sentenced to a minimum of 18 years each,

while Daniel Harrison received 15 years minimum.

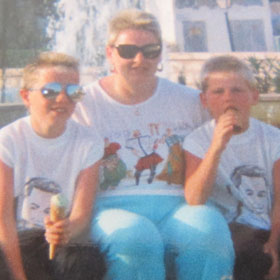

Now, as I stare at my favourite picture of the boys in their matching blue jumpers and yellow polo shirts, I know nothing will bring them back.

David was nine and Billy, six, when the school photo was taken, their whole lives ahead of them.

If I close my eyes, I can still see them, and almost touch them. But there's only barbed wire around my heart now.

I'm still not in remission but I know it'll be my broken heart that gets me. I know only too well there's no cure for that.

Sheena Faulds, 55, Glasgow

Story search...

Story archive

Just added...

From chunky to hunky

Cuddly Colin was too roly-poly to...

read more...

The boy of steel

With his baby sister Holly to love,...

read more...

The great Moggy mystery

Just what was making all of our cats...

read more...

Most popular...

Quick reads...

No choccie, but life's so sweet!

I'm a reformed chocoholic...

read more...

Baa-ck from the dead!

My heart bleated for these poor sheep...

read more...

Brave undertaking

I've swapped cars for coffins...

read more...