Stories

My life was hard to swallow

All my food came right back up...

The smell of chicken chow mein wafted up the stairs. I raced down in time to find my mum Gerri, 48, dishing up.

'Hope you've brought your appetite,' she smiled.

'Hope you've brought your appetite,' she smiled.'Course,' I grinned. I was 17 and, like most teenagers, loved takeaways. I eyed the table. If I had my way, I'd devour the lot.

Tucking eagerly into a mouthful of rice, then a forkful of sweet and sour chicken... I had to admit defeat. 'I'm full,' I confessed.

'Come on, Sophie,' Mum said, 'eat up.'

'I'm full,' I insisted.

'You can't be,' Mum said, worried. 'You only had two mouthfuls.'

Sensing her disappointment, I forced another mouthful down. Oh no, I felt sick!

I bolted upstairs, feeling rice and chicken rising back up my throat, and threw up in the toilet. Then I rinsed my mouth and sank to the floor.

No matter how hard I tried, I couldn't manage more than a couple of mouthfuls of food. Any more than that, and I puked. It had been the same since I was little.

At first, Mum and my dad Ted had put it down to jealousy. My little brother Adam was born when I was three, and they worried sibling rivalry was putting me off my grub.

They'd tried coaxing me into eating with fish fingers and chips.

But it was no good. 'You get into such a state,' Dad had said. 'Eating doesn't have to be an issue.'

It wasn't! I loved food and wanted to eat more - I just couldn't. As for being jealous of Adam - that was daft. He was my brother, I loved him.

Tragically, when I was six, Dad died of bowel cancer. He was 50. Overwhelmed with grief, I had to be dragged to school, kicking and screaming.

I'd had even less of an appetite after that, and for years everyone put it down to Dad's death. Mum tried everything to get me to eat.

Bigger plates, a huge takeaway, but nothing worked. My limit was still two mouthfuls. Sometimes, all I could eat all day was a yoghurt.

It felt like my tummy was so small, it couldn't handle any more than a couple of mouthfuls. Most days I'd be sick up to 30 times.

To make matters worse, the kids at school had made fun of me.

'Sicky Sophie,' they'd chanted.

Mum was worried and took me to the doctors. I was referred to a paediatrician who said my problem was psychological. 'You've been affected by the death of your dad.'

Of course losing Dad upset me, but vomiting had been going on ever since I could remember.

For the next few years, my weight dropped, until I was 6st.

For the next few years, my weight dropped, until I was 6st.But at least the kids weren't taunting me. 'You're so skinny,' they'd worry. 'Are you anorexic?'

Why couldn't people understand I'd love to stuff my face? Like now. There was a table full of Chinese. I'd have given anything to eat it.

The comments about my health were too much to stand. I started staying in and avoiding mates. I was becoming a hermit and hated life, was too tired to do anything.

You needed food for energy. How much longer could I carry on?

A few days later, I suffered crippling stomach pains. Looking at me bent double with pain,

Mum reached for the phone.

'I'm calling an ambulance.'

Paramedics whisked me to the Countess of Chester Hospital in Cheshire. I was fed through a tube, while doctors performed tests.

For the next three months, I lay in a hospital bed. I felt ugly with the feeding tube across my face. It was the only way of getting me the nutrients I needed, though. I was still being sick 30 times a day.

But they had no answers. So I was sent to the Royal Hospital in Liverpool. 'We need you to eat this porridge with red dye in to see how quickly food passes through your stomach,' said the doctor.

After three hours, only a tiny amount had gone through my stomach. 'You have gastroparesis, otherwise known as paralysed stomach muscles,' the doctor said.

'Your stomach muscles should squeeze together and help food pass through the digestive system. Because your muscles aren't working, you can only pass a tiny amount of food through your body.'

Finally, I had answers.

'Now we'll replace your nasal feeding tube with something that carries food into your system, but bypasses your stomach.'

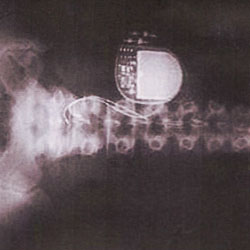

For three years, I had a tube sticking out of my nose. I'd started university in Leicester and hated going out with mates looking like I'd just been discharged from hospital. It was worth it, though. I started to put on weight. But I needed a long-term solution. I could have my stomach removed, or try a gastric pacemaker fitted into my stomach which would help move a bigger amount of food through my system.

For three years, I had a tube sticking out of my nose. I'd started university in Leicester and hated going out with mates looking like I'd just been discharged from hospital. It was worth it, though. I started to put on weight. But I needed a long-term solution. I could have my stomach removed, or try a gastric pacemaker fitted into my stomach which would help move a bigger amount of food through my system.After I'd had it fitted, we celebrated with a Chinese.

I can only eat small amounts, and sometimes need the feeding tube in my bowel, but there's light at the end of the tunnel. I've joined a support group at Aintree Hospital in Liverpool and started a counselling course. I take each day as it comes and, if there's chow mein at the end of it, so much the better still!

Sophie Bryce, 23, Northop Hall, Flintshire

Story search...

Story archive

Just added...

From chunky to hunky

Cuddly Colin was too roly-poly to...

read more...

The boy of steel

With his baby sister Holly to love,...

read more...

The great Moggy mystery

Just what was making all of our cats...

read more...

Most popular...

Quick reads...

No choccie, but life's so sweet!

I'm a reformed chocoholic...

read more...

Baa-ck from the dead!

My heart bleated for these poor sheep...

read more...

Brave undertaking

I've swapped cars for coffins...

read more...