Stories

Never been kissed

Would my little girl ever be able to show her love?

As a mum, there’s nothing quite like that feeling of tiny little kisses planted on your cheek by your son or daughter. It’s a precious memory to cherish.

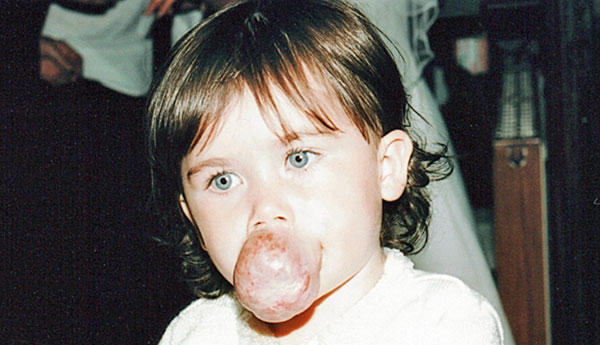

But fate had stolen that from me and my daughter Chloe, as she’d been born with a tiny, red birthmark on her lip.

At first it was a barely there, a dot you couldn’t spot in photos.

But by the time she was five months, it had grown into a bump the size of a grape over her top lip.

Doctors tried steroids, then laser surgery to remove it. But nothing worked. As our precious little girl grew, so did the birthmark.

The worst thing was, kisses were out of the question, and that broke my heart. ‘Come here, sweetheart,’ I’d say, scooping her on to my lap for a hug.

Sometimes, the urge to smother her in kisses was so strong, I’d have to fight back tears. But her lips were now hidden under a growth the size of a plum.

Despite everything, though, she developed her own way of letting us know she loved us.

One day, when she was eight weeks old, I noticed something.

‘Terry, she’s smiling,’ I said to my husband, tears welling up. ‘You can see it in her eyes.’

The birthmark made it impossible for her to move her top lip, but the look in her beautiful, big, blue eyes was enough.

‘What a lovely smile,’ I grinned.

Whenever we kissed her goodnight or went to her when she cried, instead of stretching out her arms and wanting to kiss us, her eyes would brighten.

And by the time she was toddling around, she came up with another way to show her affections. Racing up to me, she’d crash into my legs and wrap her arms tightly around them, then squeeze me.

‘What a lovely, squeezy cuddle,’ I’d giggle, picking her up and wrapping her in my arms.

Hanging down from her top lip, the lump was now so heavy she couldn’t talk properly. Somehow I understood her mumbled words and, luckily, when it came to eating, she had no problem. She’d just slip food in under her lump.

But out shopping, people stared at Chloe constantly.

Taking her to the supermarket one afternoon, I got stuck behind a man down the veg aisle. ‘Excuse me,’ I piped up, trying to push Chloe’s pram around him. ‘Sorry I just need to squeeze…’

The man turned, opened his mouth to apologise – then literally leaped back on seeing Chloe.

I felt all hot and angry. How dare he! ‘She’s just a little girl,’ I wanted to yell. ‘Don’t be so cruel.’

If only I could give her a comforting kiss.

Whenever anyone was nasty about her birthmark, I reminded myself that she would have it removed one day, while they’d always be stuck with their

ignorant attitude.

‘I prefer it when people ask what’s wrong with her,’ I told Terry. ‘Because I can understand why they might be curious. It’s better than them staring.’

I was determined not to hide Chloe away. The problem was, aged three, she was beginning to notice people’s reactions. I dreaded her first day at the nursery.

Hanging up her coat on the first day, she turned to me.

‘Why are they staring?’ she asked.

In the doorway, a couple of kids were whispering behind their hands, watching her nervously.

‘It’s because you have a special mark on your lip that no one else has,’ I said, crouching down next to her. ‘You’re special.’

‘Can I have a squeezy cuddle?’

I whispered.

Nodding, she hugged me back.

At least I knew she wouldn’t have to face nasty taunts and name-calling when she got to big school, because when Chloe was three and a half, doctors at Nottingham City Hospital would operate and remove the lump.

They’d been hoping it would shrink but, although it had stopped growing, it hadn’t got smaller.

By now, it jutted out from her top lip and hung down to just below her chin – it was the size of a tangerine.

The operation was a terrifying prospect though. There was a risk Chloe could haemorrhage during surgery and die.

But we had to try everything.

‘You’ll be fine, darling,’ I told her, putting a smile on my face.

What I’d have given to plaster a kiss on her lips.

The anaesthetist struggled to get the mask over Chloe’s face to give her the general anaesthetic because of the lump. But I was there, giving her hand it’s very own squeezy cuddle.

Four hours later, it was over – it had been a huge success.

Seeing Chloe for the first time afterwards, I gasped. ‘You can see her lips,’ I whispered.

She’d always been beautiful but now, for the first time, she looked like a normal little girl.

The only sign of the birthmark was a scar from nose to top lip, and a small, purple lump just under her right nostril.

Back home, Chloe started getting used to moving her mouth and lips.

A couple of weeks after the operation, we took her to the local chip shop to get dinner. As I was ordering, I noticed her pulling faces next to me. ‘What are you up to?’

I laughed.

She was trying her new facial expressions in the mirrored counter!

‘I look different,’ she said, pointing at her reflection.

Three weeks after her op, we’d just finished eating when she climbed on to my lap.

‘Squeezy cuddle, Mummy,’ she smiled, hugging me tight. Suddenly, she turned her head, pressed her lips against my cheek, and kissed me.

‘Oh!’ I gasped, delighted. Her first kiss! Then she launched herself at her dad.

‘Mwah!’ she said, giving him a real smacker.

It was magical. And after that, there was no stopping her.

When her little sister Ruby was born, I grinned as Chloe tenderly kissed Ruby’s tiny cheek.

Surgeons operated a second time when she was five to remove the small lump. Now she’s seven and only has a faint scar.

Speech therapy has helped, too – she’s just learned how to say ‘S’ sounds. There’s a possibility she’ll need some cosmetic surgery when she’s a teenager but, for now, she’s doing brilliantly.

After everything she’s been through, I don’t think I’ll ever take her kisses for granted. Each one is so precious.

Helen Shields, 30, Lincoln

Story search...

Story archive

Just added...

From chunky to hunky

Cuddly Colin was too roly-poly to...

read more...

The boy of steel

With his baby sister Holly to love,...

read more...

The great Moggy mystery

Just what was making all of our cats...

read more...

Most popular...

Quick reads...

No choccie, but life's so sweet!

I'm a reformed chocoholic...

read more...

Baa-ck from the dead!

My heart bleated for these poor sheep...

read more...

Brave undertaking

I've swapped cars for coffins...

read more...